Mind Links: How RFT Supercharges ABA Therapy

Mind Links: How RFT Supercharges ABA Therapy

Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) has long been recognized for its effectiveness in helping individuals with autism and developmental disabilities learn essential skills. Over the decades, ABA has evolved, incorporating more nuanced and dynamic models of language, cognition, and behavior. One of the most impactful developments is relational frame training (RFT), a structured behavioral approach based on Relational Frame Theory, which helps us understand how language and cognition are acquired. RFT enhances the reach and depth of ABA therapy by teaching not just what to learn, but how to think. This blog explores how relational frame training enriches ABA practice and why it matters in everyday therapeutic settings.

What Is Relational Frame Training (RFT)?

Relational frame training stems from Relational Frame Theory, developed by Steven C. Hayes and colleagues in the late 1980s and early 1990s. The theory explains how humans learn language through relational responding, and the training derived from this theory is designed to explicitly teach this skill when it does not develop naturally. Unlike traditional behaviorist models that focus solely on direct stimulus-response relationships, RFT-based training focuses on the learned capacity to relate stimuli in flexible, abstract, and socially significant ways (Hayes, Barnes-Holmes, & Roche, 2001).

In simpler terms, relational frame training teaches learners to understand relationships between things, even when those relationships are not directly taught. For example, a child who learns that a dime is smaller than a nickel but worth more is demonstrating an understanding of non-obvious, socially constructed relationships. This kind of relational responding—called arbitrarily applicable relational responding—is the focus of relational frame training.

Why RFT Matters in ABA

In many traditional ABA programs, the emphasis is placed on teaching discrete, functional skills such as identifying objects, following instructions, or requesting items. These are foundational and necessary skills. However, they do not always generalize well to more abstract or dynamic real-world situations. Relational frame training allows clinicians to go a step further by teaching learners how to derive new relations and apply learned concepts to novel contexts.

This training is especially important in supporting the development of generative language. Once a learner acquires the ability to relate concepts like “more than,” “less than,” or “same as,” they can begin to apply those relations to new examples without needing each one to be directly taught. This promotes independence, cognitive flexibility, and deeper understanding—areas where many individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) often need support.

Relational Frames in Everyday Learning

Relational frame training helps individuals develop various types of relational understanding. These include coordination (same as), comparison (more than, less than), opposition (opposite of), temporal (before, after), and hierarchical (category of, part of). While typically developing children acquire these relations naturally, many learners in ABA programs require direct instruction to build these relational repertoires.

For example, teaching a child that a cat and a dog are both pets helps them form a relational frame of coordination. With this frame, they can infer that pets might live in homes, eat specific foods, or play with humans. This form of relational generalization allows learners to navigate new situations with a foundation of connected knowledge, which is essential across social, academic, and everyday environments.

The Role of RFT in Teaching Perspective-Taking

Perspective-taking is a critical skill for social interaction and communication, and relational frame training plays a central role in its development. Known within the theory as deictic framing, this skill involves understanding and responding to relationships based on perspective—such as “I versus you,” “here versus there,” and “now versus then.” Many individuals with ASD struggle with deictic framing, which contributes to difficulties in social understanding and empathy.

Relational frame training teaches individuals to interpret the shifting meaning of these terms depending on who is speaking or where they are located. For example, teaching a learner that “I” means themselves, but also that “I” means something different when someone else says it, builds a flexible sense of self and other. Studies have shown that structured deictic training improves perspective-taking and contributes to social skills growth in children with developmental delays (McHugh et al., 2007).

Building Cognitive Flexibility Through RFT

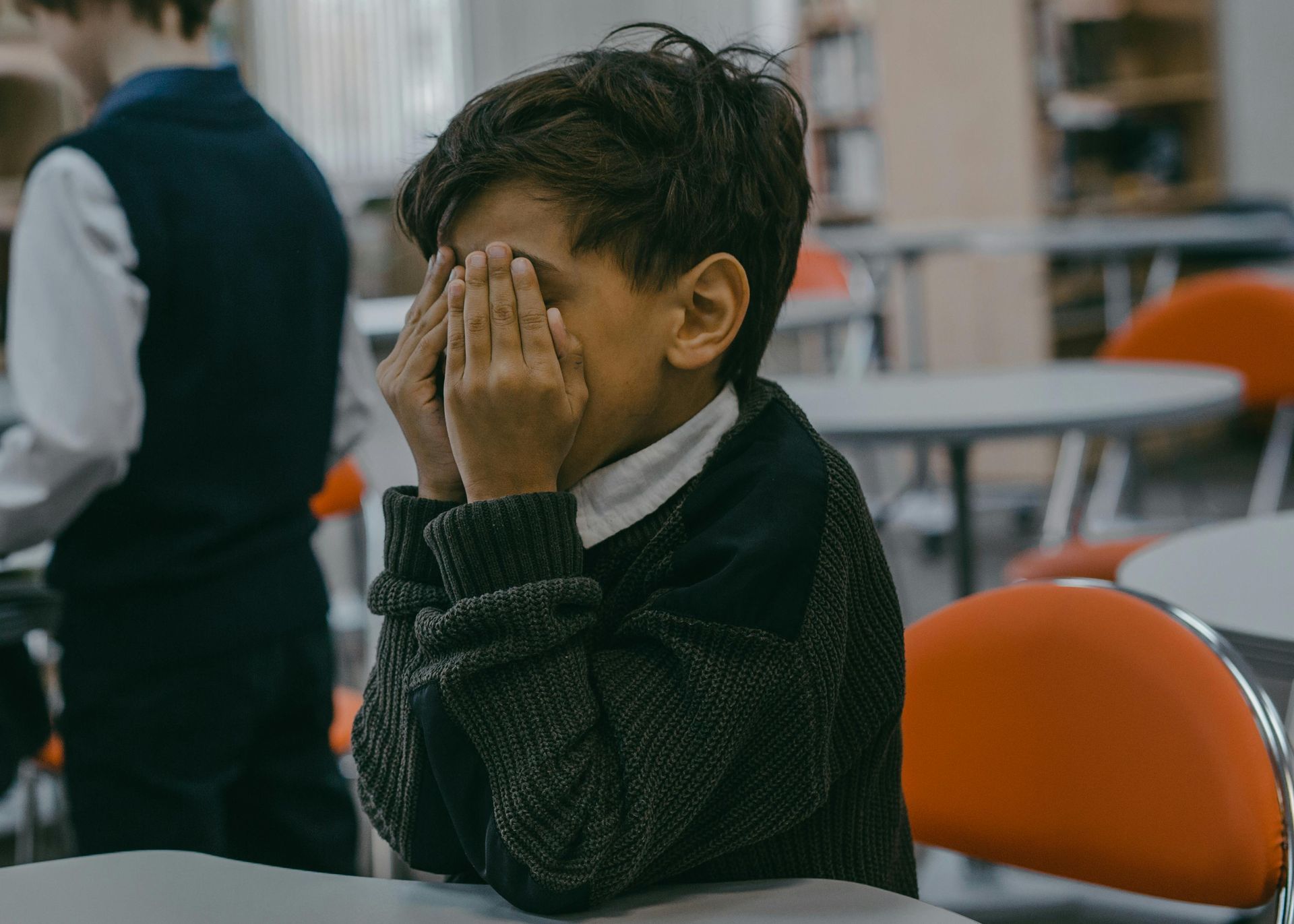

Cognitive flexibility refers to the ability to shift thinking or behavior in response to changing conditions. It is a vital component of problem-solving, learning, and emotional regulation. Individuals with autism often show rigid behavior patterns and may struggle to adapt. Relational frame training supports the development of cognitive flexibility by strengthening learners’ ability to relate concepts across changing contexts.

A simple example might involve puzzle play. A learner may first associate one specific piece with one specific location. Through relational frame training, the learner can be taught to recognize alternative solutions, infer missing pieces, or categorize pieces by function or design. This is not just a visual-spatial skill—it reflects a deeper level of flexible relational thinking.

Implementing RFT in ABA Programs

Incorporating relational frame training into ABA requires an intentional shift in how language and cognition are approached. It starts with assessing a learner’s current relational responding and identifying gaps in their relational repertoire. Programs like the PEAK Relational Training System (Dixon, 2015) are specifically designed to integrate relational frame training into ABA practices.

PEAK includes assessments and curricula that target derived relational responding. Each module builds upon basic language skills and expands into complex cognitive and social understanding. Research shows that children receiving PEAK-based instruction tend to demonstrate greater progress in areas like language development, adaptive behavior, and emotional understanding than those receiving traditional ABA alone (Dixon, Belisle, Stanley, Speelman, & Daar, 2015).

Relational Responding and Emotional Understanding

Understanding emotions involves more than recognizing facial expressions or labeling feelings. It requires understanding how events relate to internal experiences and how those experiences change based on context. Relational frame training can be used to teach emotional concepts in a more meaningful way.

For instance, a learner can be taught that losing a game is related to feeling sad, and winning is related to feeling happy. As they build more complex relational frames, they may learn that trying their best—even without winning—can still relate to feeling proud. These kinds of emotional connections support social understanding, empathy, and emotional regulation.

RFT and Psychological Flexibility

Another major contribution of relational frame training to ABA is in the area of psychological flexibility. This concept, central to Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), involves the ability to act in line with personal values even in the presence of difficult thoughts or emotions. Since ACT is rooted in Relational Frame Theory, the strategies it uses directly reflect relational frame principles.

For example, a learner who avoids a task due to anxiety can be taught to relate the feeling of anxiety with the value of trying new things. Rather than framing discomfort as a reason to avoid, the training helps the learner reframe it as part of meaningful action. This shift supports long-term behavior change and promotes engagement in valued activities (Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 2012).

Why Relational Frame Training Is the Future of ABA

As ABA continues to grow as a science and a field, its methods must evolve to address the complex needs of learners. Relational frame training offers a research-based, comprehensive way to teach the cognitive, social, and emotional skills necessary for success beyond therapy. It allows learners to move from memorizing isolated facts to thinking relationally, applying what they’ve learned in flexible, adaptive ways.

Integrating relational frame training into ABA programs doesn’t replace foundational skills—it builds upon them. It ensures that learners are not just following instructions but understanding relationships, solving problems, and connecting with others in meaningful ways.

Conclusion

Relational frame training represents a pivotal advancement in the science of ABA. Grounded in Relational Frame Theory, this training method equips learners with tools to understand, relate, and respond to their world more effectively. These mind links are the foundation of language, thought, and human connection.

By embracing relational frame training, ABA practitioners empower individuals to become more than skill followers—they become thinkers, communicators, and problem-solvers. This approach not only enhances clinical outcomes but also aligns with the broader mission of behavior analysis: to improve the quality of life for those we serve.

References

Dixon, M. R. (2015). PEAK Relational Training System: Direct Training Module. Shawnee Scientific Press.

Dixon, M. R., Belisle, J., Stanley, C. R., Speelman, R. C., & Daar, J. H. (2015). Randomized controlled trial of a relational frame training program for children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 48(4), 766–779.

Hayes, S. C., Barnes-Holmes, D., & Roche, B. (2001). Relational Frame Theory: A Post-Skinnerian Account of Human Language and Cognition. Springer Science & Business Media.

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (2012). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: The Process and Practice of Mindful Change. Guilford Press.

McHugh, L., Barnes-Holmes, Y., Barnes-Holmes, D., Stewart, I., & Dymond, S. (2007). A relational frame theory analysis of a continuously expanding perspective-taking repertoire. Behavior Modification, 31(4), 415–440.