Making Generalization Happen: From Toy Rooms to Grocery Stores

Making Generalization Happen: From Toy Rooms to Grocery Stores

How ABA Builds Skills That Stick Even in Life’s Most Unexpected Moments

When most people picture an ABA session, they often envision structured tabletop learning, colorful toys, and lots of positive reinforcement inside a therapy room. And while all that plays a role, the real magic of behavior change doesn’t happen in isolation. It happens when those carefully taught skills transfer from the toy room into everyday life. That process is called generalization, and it’s not something that just happens. In high-quality ABA therapy, generalization is a deliberate goal, planned and measured with intention.

What Is Generalization in ABA

According to Cooper, Heron, and Heward (2020), generalization refers to the ability of a learner to use newly acquired skills in environments, situations, or with people different from those where the skill was originally taught. It’s when a child who learned to ask for help with puzzles during session also asks for help at home with their shoes, or when a child who learned to wait their turn during a game can now do the same at the library. Generalization is what makes ABA meaningful. It’s what transforms therapy into independence.

In the BCBA Sixth Edition Task List, Section G focuses on behavior change procedures, and item G nineteen addresses how practitioners should program for stimulus and response generalization. This means that generalization isn’t an afterthought. It’s a fundamental part of how interventions are designed from the beginning.

Why Generalization Matters

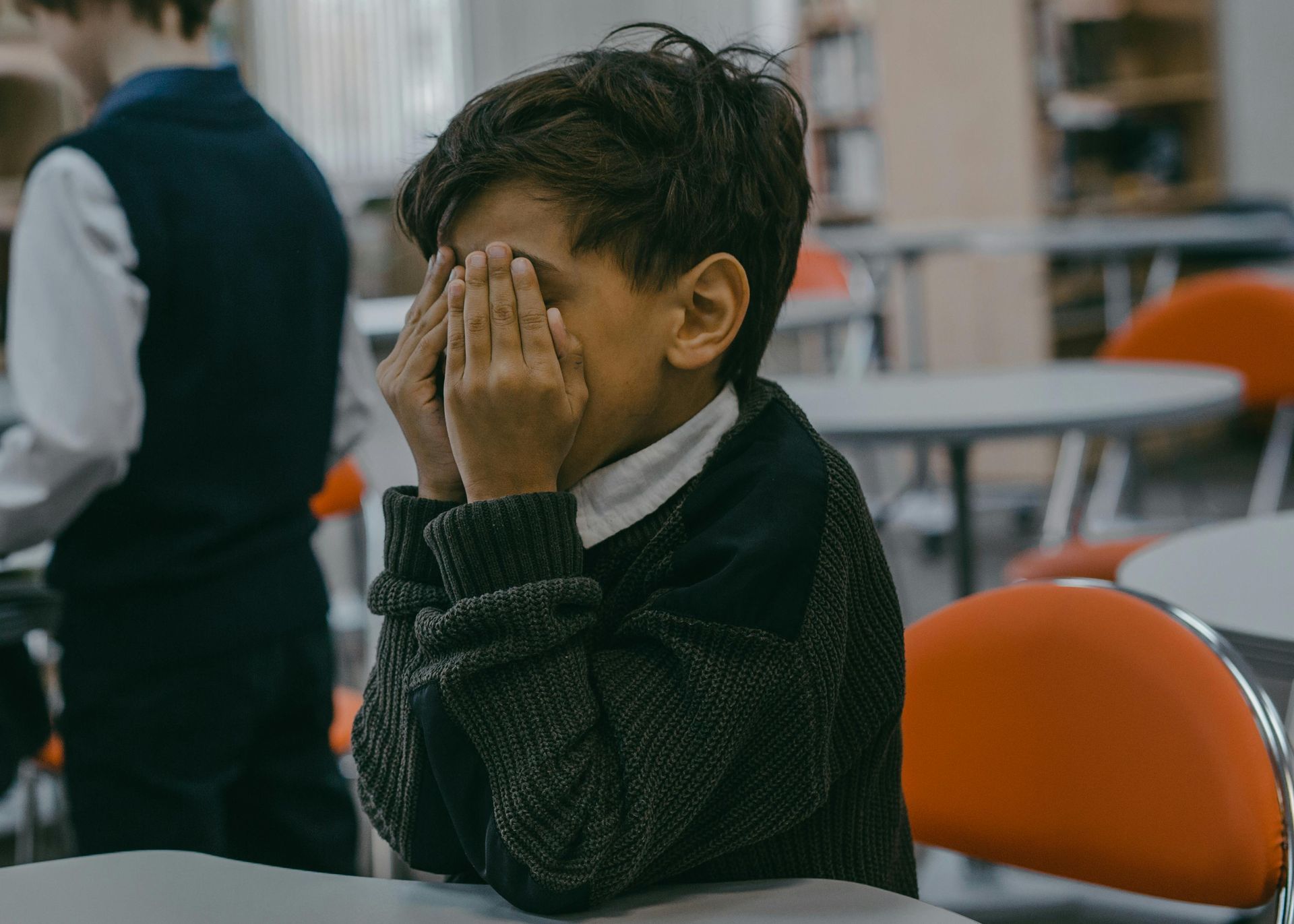

Without generalization, skills taught in ABA risk becoming robotic or situational. A child might follow directions with their RBT but not with a teacher. They might label colors on a flashcard but not in a book. In the absence of generalization, behaviors become under stimulus control of the teaching environment only, limiting their value in real world situations (Stokes and Baer, 1977).

For parents, this gap can be disheartening. You might hear, “He does it with his therapist” and wonder why those same behaviors aren’t showing up at home or in public. That’s where effective programming comes in. It’s the job of the behavior analyst to plan for generalization across stimuli, settings, people, and time. That means ensuring skills are taught and practiced with different materials or cues, in various locations, with a range of people, and sustained over time.

How ABA Therapists Promote Generalization

There are several evidence-based strategies used in ABA to promote generalization. These strategies are often integrated into play-based sessions, making learning feel natural while preparing the child to use skills across their daily life.

One effective method is to intentionally vary the people, instructions, materials, and contexts involved in teaching. For example, when teaching a child to tact apple, we might show real apples, plastic apples, apples in books, and videos of apples. We might practice with different therapists or in different rooms. By doing this, we reduce the risk of the child only responding to one specific presentation of the stimulus (Stokes and Osnes, 1989).

Another approach is to use natural reinforcement contingencies. In structured settings, reinforcement is often contrived, such as stickers, tokens, or access to a favorite toy. But in real life, behaviors are maintained by natural consequences. A child who says juice and gets a drink learns the power of requesting. ABA therapists work to fade artificial reinforcement and strengthen the behavior with natural outcomes so it persists when therapy isn’t around (Baer, Wolf, and Risley, 1968).

Teaching loosely is also key. Teaching loosely means varying the noncritical aspects of instruction so that a child becomes flexible in responding. This might include altering your tone of voice, sitting in a new place, or changing the pace of the session. This flexibility helps the child respond under less predictable conditions just like real life (Cooper et al., 2020).

ABA also promotes generalization by teaching children to prompt themselves. This includes using visual schedules, scripts, or even practicing self-talk. These tools help learners bridge the gap between therapy and independence (Koegel, Koegel, and Parks, 1995).

Caregiver involvement is one of the strongest predictors of generalization. When families practice skills at home using the same language and reinforcement strategies, the skill is more likely to transfer beyond therapy (Brookman Frazee et al., 2009). That’s why parent training isn’t just helpful. It’s essential.

Generalization is closely tied to maintenance, which refers to the continued use of skills over time. We don’t just want a child to say hi once to a peer. We want that skill to show up months later, in different environments, with new people. Programming for both ensures the skill becomes part of who the child is, not just what they were taught.

From Toy Rooms to Grocery Stores: What It Looks Like in Real Life

Let’s imagine a child named Mateo, who is working on functional communication and waiting his turn. In the therapy room, Mateo has learned to use a speech device to request a car during play and to wait his turn for the slide. Here’s how generalization might be programmed.

At home, Mateo’s therapist coaches his caregiver to model the same button on his device when they play with toy cars. During a grocery store trip, they pause near the toy aisle and give Mateo a chance to request a preferred item using the same sentence frame. Later, at the park, Mateo’s sibling and a BCBA both practice turn-taking games with him, sometimes with swings, sometimes with balls. In these small but deliberate ways, the skill goes from isolated to integrated. Mateo doesn’t just know the skill. He owns it.

Common Barriers to Generalization

Even with careful planning, generalization can be challenging. Some common barriers include over reliance on specific staff or materials. If a child can only perform a skill with one therapist, it may not generalize. Inconsistent reinforcement across environments can also hinder generalization. If parents or teachers don’t follow through with reinforcement strategies, the behavior may extinguish.

Failure to teach flexible responding is another obstacle. If a child is only taught to respond in one specific way, they may struggle when conditions change. Emotional variables such as high stress or busy public settings like a grocery store may inhibit performance even when the skill exists.

This is why generalization must be embedded from the start and monitored regularly with data. It’s not a bonus feature. It’s a critical, ongoing goal.

The Role of the BCBA in Generalization

BCBAs play an essential role in designing and monitoring generalization strategies. According to Task List item G nineteen, practitioners must program for both stimulus and response generalization from the start. This means choosing goals that matter across contexts, designing teaching environments that mimic the real world, and collaborating with caregivers to provide coaching and modeling.

BCBAs also use data to monitor whether generalization is occurring. If a child can independently complete a task with one therapist but not with another, or can do it in the clinic but not at home, that’s a red flag. Ongoing probe data in varied settings help us make evidence-based decisions about what to modify.

Empowering Parents to Support Generalization

Parents are not passive observers in the generalization process. They are key partners. The most successful ABA programs include caregiver coaching where parents are trained to use consistent prompts and reinforcement, embed skill practice into routines, fade support as the child gains independence, and create opportunities for natural learning. Parents don’t need to become therapists, but they can become powerful agents of change when guided by a collaborative and compassionate team.

Why It All Comes Down to Dignity and Meaningful Change

Ultimately, generalization isn’t just a technical skill. It’s a matter of dignity. It means teaching a child to navigate their world with confidence. It’s helping a child greet a new friend, follow classroom routines, ask for a break when overwhelmed, or order their favorite meal. These are the building blocks of independence, community participation, and belonging.

Play based ABA provides the perfect platform for this. Through play, children learn flexibility, problem solving, and communication in ways that feel joyful and motivating. When paired with strong clinical programming, these sessions create a bridge between therapy and the real world.

So, the next time you see a child stacking blocks, singing songs, or pretending to cook in a toy kitchen, remember they’re not just playing. They’re learning skills that will follow them into classrooms, kitchens, and grocery store aisles. With intentional programming, those skills won’t stay in the therapy room. They’ll walk out the door with them.

References

Baer DM, Wolf MM, and Risley TR. (1968). Some current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 1(1), 91–97. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1968.1-91

Brookman Frazee L, Stahmer A, Baker Ericzén M, and Tsai K. (2009). Parent perspectives on community mental health services for children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 18, 709–725.

Cooper JO, Heron TE, and Heward WL. (2020). Applied Behavior Analysis (3rd ed.). Pearson.

Koegel LK, Koegel RL, and Parks DR. (1995). Teach children with autism Strategies for initiating positive interactions and improving learning opportunities. Paul H. Brookes Publishing.

Stokes TF and Baer DM. (1977). An implicit technology of generalization. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 10(2), 349–367.

Stokes TF and Osnes PG. (1989). An operant pursuit of generalization. Behavior Therapy, 20(3), 337–355.