Acceptance and Commitment Training in ABA Practice: Cultivating Psychological Flexibility for Meaningful Change

Acceptance and Commitment Training in ABA Practice: Cultivating Psychological Flexibility for Meaningful Change

Applied Behavior Analysis is rooted in the science of behavior and environmental relationships. It teaches us to look at what comes before and after behavior to understand its function. Acceptance and Commitment Training, or ACT, complements this by offering a systematic way to address internal events such as thoughts and emotions in a behaviorally consistent and effective manner. ACT is grounded in Relational Frame Theory and radical behaviorism and promotes psychological flexibility, which is the ability to act in ways that align with personal values even in the presence of difficult thoughts or emotions (Hayes et al., 2006; Dixon and Paliliunas, 2017). This process enhances how we support clients across populations, including those with Autism Spectrum Disorder and those without any diagnosis.

Making Values-Driven Decisions While Navigating Challenges: The Process

Psychological flexibility is the foundation of ACT and refers to behaving in meaningful ways despite experiencing emotional discomfort, cognitive rigidity, or physiological distress. It involves six interrelated processes. These include acceptance, cognitive defusion, contact with the present moment, self-as-context, clarification of values, and committed action. When each of these elements is applied within ABA programming, it enhances the learner’s ability to navigate life’s challenges, make values-driven choices, and persist in adaptive behavior patterns.

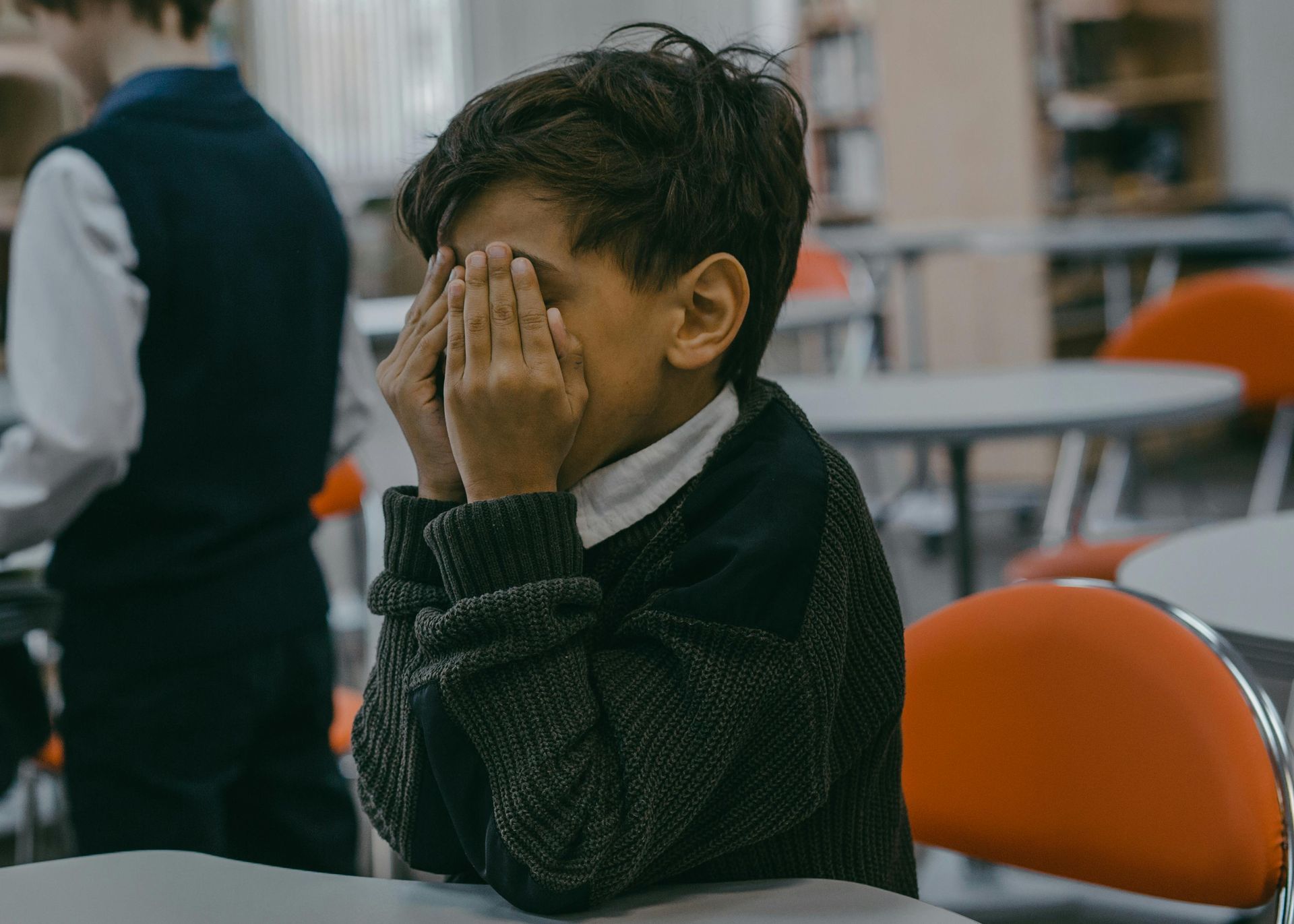

Accepting Feelings of Discomfort

Acceptance means helping individuals open up to uncomfortable internal experiences without attempting to change or avoid them. In traditional ABA, escape-maintained behaviors are often addressed by adjusting task demands or reinforcing toleration. With ACT, analysts go a step further by teaching clients that it is okay to feel nervous or frustrated. Instead of eliminating discomfort, the goal becomes increasing willingness to experience those feelings while still engaging in valued behavior. For example, a child who feels anxious about speaking in front of peers can be taught to acknowledge that anxiety without needing it to disappear before participating in the activity.

Cognitive Defusion: Reducing a Thought's Control Over Actions

Cognitive defusion involves altering the way individuals interact with their thoughts. Rather than accepting a thought like “I can’t do this” as absolute truth, ACT teaches clients to see thoughts as passing experiences that do not have to control behavior. This is particularly helpful for clients who experience rigid rule-following or avoidance based on self-critical thinking. In ABA, this might look like a learner labeling their thoughts by saying, “I am having the thought that this is hard,” which helps reduce the thought’s control over their actions. The introduction of this process in behavior intervention allows the learner to remain in contact with the environment rather than retreating due to their internal dialogue.

Contact with the Present Moment to Reduce Impulsivity

Contact with the present moment emphasizes being aware of the current environment and internal experience without judgment. In ABA sessions, this can involve prompting learners to take a moment to breathe, describe what they notice around them, or identify what they feel in their body. These mindfulness practices support regulation, help reduce impulsive responding, and increase on-task behavior by grounding the learner in the current context. Present moment awareness is especially valuable in helping learners navigate transitions, tolerate delays, and manage unexpected changes.

Self-As-Context: Fostering Resilience & Compassion

Self-as-context refers to the stable sense of self as the observer of thoughts and experiences rather than being defined by them. Many individuals, particularly those who have experienced repeated failure or criticism, fuse their identity with negative thoughts. ACT supports the development of perspective-taking, encouraging learners to recognize that they are not their thoughts. A teenager who says, “I’m not good at talking to people,” can be guided to see that this is one experience among many, not a fixed truth. This process fosters resilience and allows for a more flexible and compassionate relationship with the self.

Clarification of Values to Achieve Long-Term Goals

Values clarification plays a central role in ACT by helping individuals identify what truly matters to them. In ABA, goals are often selected based on functional outcomes. When those goals are explicitly linked to a learner’s personal values, their motivation increases, and the behavior becomes more meaningful. For instance, if a young adult values independence, then tasks like managing a budget or initiating job-related conversations can be taught in a way that ties directly to that value. This helps the learner understand the purpose behind the behavior, increasing buy-in and long-term engagement.

Committed Action: Aligning Tasks with Personal Values

Committed action refers to taking steps aligned with personal values despite discomfort or obstacles. This process mirrors how ABA uses shaping, chaining, and reinforcement to build complex behavior. When a learner is taught to persist with a task because it aligns with their values rather than because a reinforcer is offered, the behavior becomes more intrinsically driven. In practice, behavior analysts can teach learners to identify the next smallest step toward a meaningful goal, acknowledge any internal resistance, and still choose to act. Over time, this leads to increased autonomy, emotional maturity, and behavioral consistency.

When ACT is incorporated into ABA programming, it enriches goal setting and implementation. Traditional behavior goals such as increasing communication, tolerance, or social interaction can be enhanced by including ACT-based objectives. For example, a learner’s program might include not only increasing spontaneous mands across three settings but also identifying and accepting thoughts related to rejection or anxiety that previously interfered with requesting. These internal process goals can be tracked using client self-report, therapist observation, or structured check-ins.

Social Stories: Using Narratives to Prepare for Uncomfortable Situations

Social stories provide a powerful tool for incorporating ACT concepts into teaching routines. These narratives, often written in the first person, describe a situation, the appropriate behavior, and how the individual might feel. When ACT is embedded in social stories, the learner gains both a behavioral roadmap and a psychological one. A story about preparing for a dentist visit can include language that models acceptance of worry, encourages noticing thoughts like “This will hurt” without judgment, connects the visit to a value such as health or bravery, and guides the learner to follow through with action. This format not only supports skill acquisition but also teaches learners how to navigate discomfort, making generalization across settings more likely.

Generalization: Applying Learned Skills in Natural Environments

Generalization is a cornerstone of both ABA and ACT. One of the biggest challenges in applied work is helping clients carry over learned skills into natural environments. ACT processes are inherently portable and context-independent. Whether at home, in school, or in the community, individuals can use defusion phrases, awareness cues, and value reminders to persist with behavior that supports long-term outcomes. A learner who practices defusion during session can apply it while waiting in line at a store. Another learner who uses self-talk to manage nervousness about asking for help in the clinic can carry that skill into the classroom or workplace.

Beneficial to Emotional Regulation & Resilience

ACT-based approaches benefit not only individuals with ASD but also those without any diagnosis. Parents, siblings, teachers, and behavior technicians all experience frustration, fear, self-doubt, and stress. ACT provides tools to increase psychological flexibility in these stakeholders, enhancing collaboration, reducing burnout, and improving communication. Studies have shown that ACT-based parent training can improve parents’ emotional regulation and resilience, which in turn supports more consistent and compassionate parenting (Tarbox et al., 2023). Similarly, ACT integration within staff training has been shown to improve fidelity and generalization of behavior support procedures (Little et al., 2020).

Implementing ACT within ABA practice begins with assessment of both overt behaviors and covert experiences. Analysts can gather information about when avoidance or fusion occurs and what internal content might be maintaining problem behavior.

Interventions are then designed to teach acceptance, defusion, mindfulness, and values-aligned actions alongside traditional behavior analytic strategies. Measurement systems include both observable data and qualitative tracking of ACT processes, such as frequency of acceptance statements or learner-reported value alignment. Over time, these additions result in behavior change that is not only measurable but also deeply meaningful.

In conclusion, Acceptance and Commitment Training offers a powerful and compassionate framework for enriching ABA practice. By addressing the internal barriers that interfere with learning, ACT helps clients develop psychological flexibility, build resilience, and live in accordance with their values. Embedding ACT processes within ABA sessions, social stories, and everyday routines supports generalization and promotes long-term success. Whether working with individuals diagnosed with ASD, their families, or the broader community, ACT-based interventions empower people to engage more fully with life, even in the presence of discomfort.

References

Dixon, M. R., & Paliliunas, D. (2017). Acceptance and commitment training and therapy in applied behavior analysis. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 10(2), 146–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-017-0198-9

Gray, C. (2015). The importance of embedding emotional awareness and acceptance in social narratives. In Social Narrative Interventions.

Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F. W., Masuda, A., & Lillis, J. (2006). Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes, and outcomes. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006

Little, A., Tarbox, J., & Alzaabi, K. (2020). Using acceptance and commitment training to enhance the effectiveness of behavioral skills training. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 15, 31–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.01.003

Tarbox, J., Szabo, T., Aclan, J., et al. (2023). Parent, child, and family outcomes following group-based ACT for parents of autistic children. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 53, 1450–1463. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613231172241